The usual summary of comic book artist Will Eisner’s career follows the formula that he drew the Spirit all through the 1940s except for the war years and a bunch of ‘graphic novels’ from 1978 till the end of his life in 2005. There’s a long missing period between 1951 and 1978 during which he packaged and adapted cartoon art to commercial purposes, which has not been readily available for our scrutiny or pleasure. It is sometimes summarily dismissed as being of little interest.

The last time I wrote about Will Eisner’s 'middle period,' was in defence of the artist in a letter to the Comics Journal (#270) following publisher Gary Groth’s piece in their big Eisner obituary issue (#267) which could only be explained as spiteful. I though it was unnecessary, not because it was an inappropriate time, but because it was… unnecessary. Not wanting to allow my comments to stand isolated, Gary hemmed them in with another batch of his own (much as I am doing here in return), from which I quote:

“I’ve seen the litany of banal explanations for Eisner’s abandoning of the art form for the world of business… I acknowledge that it’s eminently possible that we have reached the point where a training manual for the pentagon or an informational educational story arguing against national health care is indistinguishable from an artist’s exploration of the human condition, and refraining from lamenting this state of affairs is not so much uncivilized as a bourgeois evasion.”I cannot see, as I get further and further from my eleven-year-old self who first read Eisner in 1966, how the cranking out of a weekly comic book for twelve years about a mask-wearing hero can be art of a sort but turning the same techniques to an instructional magazine about equipment maintenance for living, working soldiers, cannot be. I’m sure Eisner and most reasonable beings saw and see them both as commercial enterprises.

Groth's position furthermore implies that Art is owned by one social group, in this case one which is counter-cultural in a capitalist society, an argument that is not to be taken seriously in these culturally democratic times. The 'bourgeoisie,' whoever they might be, a vague notion of the middle classes that one might still encounter in reading about Marxist rhetoric, are as entitled as any other group to see their interests reflected in art, and we can hardly blame them for the grotesque extravaganza of baloney that surrounds us today. I have no interest in the journalistic myth that art and commerce are manichean opposites, and whether you call a thing Art at all is neither here nor there. It is what it is, separate from all our blather.

I was defending Eisner’s lost period on principle then, but now I am systematically reading, or at least scanning with my alert eye for much of it, every page of the entire run of Eisner’s PS: The Preventive Maintenance Monthly, thanks to

Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries who have put it all online. I'm up to the end of 1956 as I write this. I may have different feelings about the material before this date than I will have of the period after it, as I suspect that the quality will taper off somewhere along the line. I'll let you know when I'm done, next week probably.

It’s a technical publication: how to clean a rifle, how to defrost a jeep battery, how to cut down trees, with hard information provided by the upper echelons of the military and dressed up for the soldier’s edification in lively humorous typographical settings. While it announces itself as a monthly mag from the start, it appears intermittently for three years before obtaining regularity, presumably an experimental phase when the plan was still being worked out. It is noteworthy that for one whole early issue, #14 (a special issue devoted to tanks), Eisner's crew seems to be missing altogether. The result is an uninviting textbook. Elsewhere the Eisnerian settings humanize the lessons and succeed in removing me to a distant time and place where I start to care about the proper way to fill out an Unsatisfactory Equipment Report (UER form 4G8), and be glad that I learned in time to

“... stick to the “block” method of adjusting track tension on your late M48 and T67 (flame-thrower) tanks with their tension idler wheels."#48, Sept. 1956

Eisner’s personality is peppered all through it, though inevitably moreso in some places than in others. There are densely illustrated passages and also long stretches where you could easily give up hope if you have not waited as long as I have to see this stuff. If you have limited time to go looking, I've marked issues 17, 21 and 47 with five stars. To put the info across he created a handful of characters who mostly only exist in the always refreshed banners that run across the first pages of their regular spots in the mag, and I find myself acquiring an affection for them as they exist as much in the imagination as any character who ever had a fleshed-out story-life. ‘Sgt. Half-Mast McCanick’s anwer Dept,’ ‘Windy Winsock’s Windstorms,’ ‘Connie Rodd’s Short 'n Sweet dept.’

#46, July 1956

There was always (with a couple of early exceptions) a pull out spread in the middle of the mag titled ‘Joe’s Dope Sheet,' captioned by an amusing limerick. Here’s one with a delectable study of Connie in long johns:

#25, Sept 1954

Joe Dope got the regular comic story in the middle that appeared in the 8-page colour section around the pull-out, and Connie always appeared there too. Sometimes it’s a good funny read and other times the characters are just explaining some form or piece of equipment. The best of these are as good as anything by Eisner. Sometimes It’s clear to my eyes that Eisner isn’t quite present on the job, but that doesn’t necessarily matter as there were people on his team who are worth collecting in their own right. I’m not certain who the artist on this one is. It could be Klaus Nordling.

#27, Nov. 1954

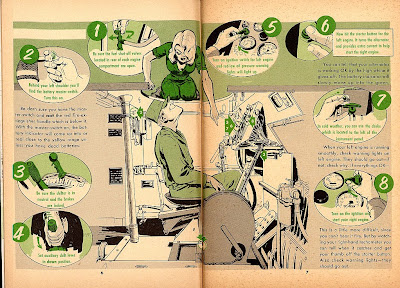

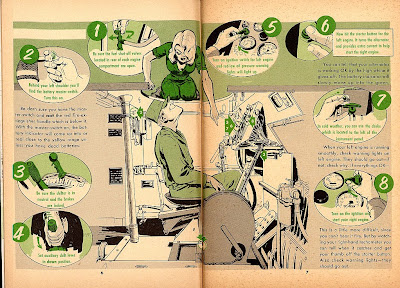

The rest of it is more interesting or less depending on how much thought Eisner's crew put into the job. You can find a few spreads that sing with a particular kind of comic book vitality. Ordinary typesetting is embedded in a spacial cartoon environment to make the eyes feel at home; come in, have a look around.

#26, Oct 1954

I love the way the one extra colour is handled in some of these, and it changes from issue to issue.

#21, May 1954

There's another kind of spread that awakens an old enthusiasm in me. That is the 'cutaway'. Here is a cutaway of the M59 Armored Infantry Vehicle:

#46, July 1956

Looking at the cutaway picture above makes me think that my appreciation of this technical stuff dates back to that particularly British childhood joy of the old Eagle cutaway spreads in the late fifties/early sixties. Like so many of my contemporaries, I was a boy who couldn't get enough of that stuff. I see there was a book collecting the best of them that was published last year. There's a review of it at

The Fold. And another at

Eagle Times. which includes a comprehensive list of all the artists who worked on them.

Steve Holland looks at the work of Leslie Ashley Wood, one of the best of those artists.

Jeremy Briggs at Down the Tubes covers it too, from where I've pinched this image of a presumably fanciful hover-truck painted by Geoffrey Wheeler:

Max Gadney,

Cutaways in Information Graphics, muses on the impossible complexity of some of those images

"...on the one hand it shows the futility of showing that amount of detail to the average reader - yet it belies the reasons that people (especially tech minded ones) like cutaways - because they are not reading about where an engine is on a rocket ship - they are dreaming about building one."My browsing finally led me to a phrase that suggests where this line of enquiry is ultimately leading:

Information aesthetics. Where form follows data.There's a new book coming out on the subject of Eisner's PS magazine and I look forward to getting my hands on it. I'm hoping it will fill in the kind of details I love, such as who ghosted that colour Joe Dope page above.

"The author, Paul E. Fitzgerald, was the magazine’s first managing editor. He weaves together two parallel stories—Eisner as an artist in expansive change, and the U.S. Army’s daringly innovative publication that moved from early perilous survival and bureaucratic brinkmanship to 58 years (and still going) as a sweepingly successful communications pacesetter.

The author’s knowledge of PS operations and challenges, production techniques, and personalities, coupled with his ongoing personal and professional friendship with Eisner from 1953 until the artist’s death in 2005, provides a unique and close-up look at the “middle period” of Eisner’s creative life."Far from lamenting Eisner's long disappearance into this line of work as a waste, on the contrary I am momentarily regretting the years I myself have wasted creating fictions when I could have been giving the world something useful.

Labels: Eisner