A

About these 'RULES' of mine. I originally collected and numbered them for a talk I gave, which I titled 'Towards a rhetoric of comics'. In other words, a bunch of principles codified for assisting a cartoonist to put his thoughts across in the clearest and most persuasive way.

Jessica Abel drew a two page comic strip explaining how a comic strip works, and I have a problem with it. I don't think it's Jessica's fault. She has tried to explain something which under closer scrutiny proves to be faulty, but she's too sweet to say so. Now, me, I'd say: "this system is shambolic, I'm proposing a new one whether you like it or not."

The problem lies in the placing of word balloons. Convention (or Jessica) says that comics are a 'nested system'. You read a panel from left to right and from top to bottom and, when you've read everything in that panel you move left-right and top-bottom and read everything in the next one until you've completed the page.

However, in all of my watching and noting over many years, the reader, even the experienced one, after reading the contents of a balloon, will be inclined to read the next nearest balloon irrespective of whether the rest of the balloons in the current panel have already been taken in. If the next nearest balloon is in the next panel, or even the panel underneath, then the cartoonist risks losing control of his/her narration. Therefore the very first thing the artist must do upon a approaching a page is pin down the balloons. In fact I go so far as to do all of the lettering first, because in addition to the above, lettering will take much less reduction in size than a picture, therefore it is essential to give the lettering priority. When I am certain that the lettering follows reading-logic, only then do I start drawing. Each balloon should follow clearly from the one before it no matter where the panel borders are placed.

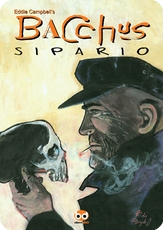

example a: a page from Bacchus vol 1,

Immortality isn't Forever (right above). The first panel is the tall one at the left of the page. My system dictates that the lettering in this panel go at the very top and there only, even though it might function better nearer to the heads of the speakers, otherwise the reader would be required to break a basic reading rule and move up the page to the next panel and its balloons, instead of following the conventional law of top-bottom.

example b

example b: page at pencil stage from my cockeyed version of the Minotaur's story in Bacchus vol 3,

Doing the Islands with Bacchus. lest you think that my system is inevitably going to require that all the balloons float at the tops of the panels, here's a variation. In this case the position of the balloons in the second panel have determined that those in the last panel must be placed very low, in fact at the foot of the page. The course of the balloons follows a downward sinuous line. They can only be read one way. This sample is also useful in that you can see I have ink-lettered the balloons while the pictures are only sketched roughly. In fact if you have the book you'll know that these pictures were replaced by others at the inking stage. I wouldn't normally do this much sketching (any) before lettering except that this was an odd layout that required special attention.

To summarize:

CAMPBELL"S RULE #3: In spite of what you may read, comics are not a nested system; a reader will read a balloon and then read the next nearest balloon even if they haven't already read all the ones in the current panel.

Other relevant thoughts on the general subject of balloons: Eisner has stated that giving a character more than one balloon in a panel gives the lie to the panel being a moment in time, with characters frozen in a pose relevant to what they are saying (therefore they can only be saying a limited amount). We all have our rules to make our specific way of doing things into a coherent system, but I don't worry too much about that one (you take your pick). I distrust the idea of comics being tied to 'time'. it's too close to the movie model for my liking. And there are bigger lies to worry about, like who said they didn't steal the tarts, or said they didn't kill Cock Robin.

Alex Toth wrote something about lettering that stuck in my head.

It may have been here but I can't find it again. That site has Toth doing commentaries on a bunch of his old short stories. The 50s romance stories are the ones most worth checking out. He said that he liked a lot of 'padding' in the balloons, in other words, a comfortable amount of white space around the block of text. I have taken that one on board completely.

At the top of this post is a brace of word balloons from a detail of a panel in

The Black Diamond Detective Agency that express my present aesthetic ideal. The balloon should be a thoughtfully designed shape that relates to the things around it in its pictorial context. I absolutely DETEST and ABHOR those goddam elipses they use nowadays in the comic books. I LOATHE them and will NOT TOLERATE them. I also don't care for them. I've heard all the economic arguments, so don't send them to me. Within the balloon the block of lettering should also form a designed shape, which need not echo the shape of the balloon around it, but the two should be aware of the existence of each other. It need not be said that I also have no time for computer fonts. But thirdly and don't forget this one, the space between the block of lettering and the balloon is a yet another element that needs to be carefully considered and shaped, the 'padding ' that Toth speaks of. Half close your eyes and you'll see it as a white stream flowing around the block of text.

In my last couple of jobs I have taken to painting the balloons onto the page of art (before the picture, and then tidy them up later) in a pale yellow. I want the balloon to be a painted presence on the page instead of a hole through it to another dimension. I arrived at this by an evolutionary process after I started doing the painted books (in

Batman: Order of Beasts I used a font, with irregular balloon shapes but with a holding line around them. The holding lines proved to be a technical pain in the ass, so in the 13 page Escapist story I did I tried losing those and lettered onto a tracing paper overlay by hand, which is very simple to align with the time honoured manner without extra computer work. This proved satisfactory so I carried the approach over to

Diamond and I'm also using it on my new one,

The Amazing Remarkable mr. Leotard.

My pal Dave Gibbons felt compelled to throw in his two cents on my last 'rule' . Since he does his own lettering and it is always faultless, I'll be very interested indeed to hear his thoughts on this one .

Finally, if you click the 'balloons' label below you'll find an earlier post on the subject.

Labels: Bacchus 1, balloons, my rules