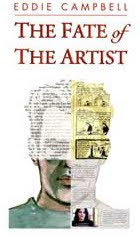

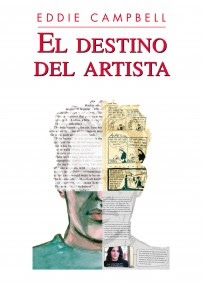

I was glad to catch Bryan Talbot in conversation this week before we appeared on stage, because I know we don't see eye to eye on a lot of aesthetic and historical matters, and I wanted to get them out of the way in case we embarrassed ourselves publicly. So I found myself in an interesting technical discussion which can be nicely extended into an essay here. Bryan criticised my 'fumetti' sequence in The Fate of the Artist, in which hayley campbell is interviewed about the disappearance of her beloved father. Here is the first page of it. Ignore the obvious goof in panel 1 of attributing the interviewer's question to the subject by encircling it in a lasso resembling, for the sake of this discussion, a speech balloon.

The seven page hayley sequence is intended of course to evoke the 'fumetti' idiom, the English language name for a style of comic strip that is said to have originated in Italy, in which photographs take the place of drawings. Here is an attractive example of the style (Check here for the whole work in 36 panels, by Charlie Beck)

Bryan said to me that he feels that the hayley passage fails because he doesn't believe the character is actually speaking. I said, what, you mean the thought processes are not convincingly those of a nineteen year old girl? Bryan replied, no, I mean the face in the picture doesn't correspond to what is being said in the balloon, and the mouth isn't even open. Ah. the conversation didn't get much further because I was taken aback; it was something I hadn't even thought to prepare a defence for. I do say clearly that it's a transcript of a taped interview (entirely a fiction), and I've taken pains (as has Mick Evans, who brought the parts together at the design stage) to make it look roughly cut and glued from a typeset document; it's NOT direct speech. There is no sound.

I worked hard to avoid the kind of histrionics you see in the second example above, in which skill and craft are evident but inauthenticity is the initial impression. It has a feeling of being staged (though note that Beck arrived at the same conclusion I did, that a series of open mouths on one character looks too wrong). Talbot's seven page episode of fumetti in his Alice in Sunderland is so something else that it would seem eccentric to make a comparison. It's perfectly appropriate to his purpose.

So let me stick to the subject of the word balloon, which is the real issue here, and it dovetails with an earlier discussion I had with Bryan. In the following example, do we believe that the 2,000 year old bust of Caesar is LITERALLY SPEAKING the words from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar?

Or would we say: no, it's not direct speech but a quote contained in a balloon of attribution which combines with the image to make a graphic construct at the same time more direct and more complex than the sum of the elements. Note that in an earlier version I had the quote "I came, I saw, I conquered," but ditched it as the words looked too simply like words that ought to go with the face.

The earlier discussion (with Bryan) concerned my assertion that we should not corral willy nilly under the rubric of 'comics' old works that appear to have the same formal elements, because there is a tendency to misinterpret their function, for example the word balloon. The most intelligent view on the subject is the 22 page essay, On labels, loops and bubbles by Thierry Smolderen in Comic Art #8. He writes:

Throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, labels consistently appeared in political satires. Because their function seems, at first glance, similar to that of the 20th century device, the modern reader is tempted to read them as regular speech balloons, ignoring the fact that there isn't anything remotely similar between a 20th century comic strip and a 17th century allegory...

In an allegorical picture, each character (or, sometimes, object) has both a literal and a metaphorical meaning. On the literal level, the picture can mean just about anything - or make no sense at all; the 'tableau' is merely a hieroglyph; its external appearance needs not be more plausible or coherent than the garbled letters of a cipher. Thanks to this freedom, the satirists were allowed to combine topical interests with any wild fancy of their imagination...

In such a context, the reason why the labels cannot be read in the same way as our modern speech balloons becomes clearer. Nothing is alive or natural in allegorical constructs: like rebus riddles, they exist in a timeless and spaceless dimension, in which no living sound will ever travel. How could metaphors freely dialogue between themselves like characters in a comic strip? Any verbal exchange included in an allegorical picture could only be the metaphor for something else.

(example from an 1860 Currier and Ives print used in the article)

I think the real difference between Bryan and me is that he likes and believes in 'comics,' (see his three page history of British comics in the Guardian last week) and imagines I do also, but I don't. It is a medium that becomes more conservative and moribund every year. All the theories are designed to shackle it to a metronome of measured time analogous to the cinematic. Give me an art that doesn't need to constantly resubmit its claim to the respect that readers award to the 'realistic,' which must dress the facile in verisimilitude. I want a truth that has no need to play games of make-believe.

p.s. Of course, on Bryan's behalf I should say that in order to do what they do, artists need to be single minded to the point of thinking everybody must do things their way. For example I remember Pekar criticising Spiegelman for using animals in

Maus. And God knows what innocent Charlie Beck thinks of me for dragging him into my argument. Check his page and lighten my guilt.

pps. re talking things that are not literally talking, see

my post on Rome's 'talking statues'.

Labels: balloons, fumetti